Beware of Tularemia

Re-Stacking and posting here a post from Dr. Richard Horowitz from his Substack.

Beware of Tularemia!

by Richard Horowitz MD

Thanks to a warming climate and larger acorn crops (which increase the tick-carrying mice population), 2025 has become a banner year for ticks. You need to know about all the potential tickborne diseases (TBDs) you can be exposed to, and you can go to the links at the end of this Substack to see what I’ve already written about Lyme disease, Babesiosis, Bartonellosis, Ehrlichiosis, and Anaplasmosis.

Let’s add tularemia, a potentially severe infectious disease with a broad range of clinical manifestations, to the TBDs list.

In the US, the primary tick species known to transmit tularemia are the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), its primary vector; the wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni); and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum). Deerflies (Chrysops spp.) can also transmit tularemia, particularly in the western US.

What Causes Tularemia?

Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis, a gram-negative intracellular bacteria. Often called rabbit fever or deerfly fever, transmission can happen from multiple routes (skin, oral, inhalation), making it widespread in the environment and extremely infectious. As few as 10 organisms are capable of causing severe disease! Look at this image of numerous gram-negative Francisella tularensis coccobacilli and imagine how badly infected this person was….

The extreme infectivity of F. tularensis, and its ability to be transmitted via multiple routes potentially causing severe illness is why this disease is not a usual TBD—these factors also make it a potential bioterrorist threat. Its high infectivity rates, being relatively easy to culture, with no vaccine, and ability to spread via aerosolized droplets makes it a formidable pathogen. Each time I’ve found tularemia antibodies in my patients, I’ve gotten a call from the health department, and I had to reassure them that a tick was responsible, not bioterrorists! It is a significant public health concern, warranting a comprehensive understanding of its manifestations, diagnostic approaches, and treatment strategies.

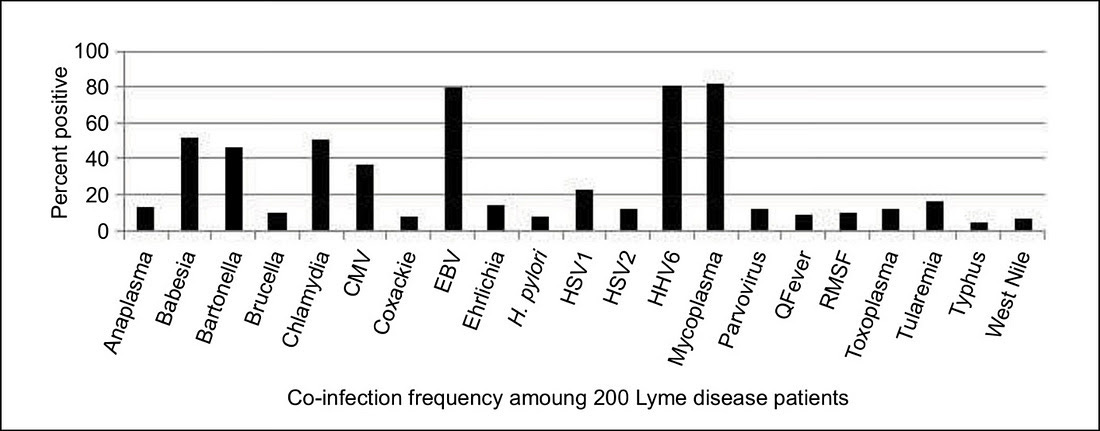

In a study my colleagues and I published in the International Journal of General Medicine in 2019, during a retrospective review of 200 patients undergoing dapsone combination therapy to treat chronic Lyme disease/PTLDS, we found that the 16.5% of our patients had tularemia antibodies.

Those with low positive tularemia antibodies may not have true tularemia (see below), but those with 4-fold increases in antibodies and associated clinical manifestations can and do manifest with different forms of the disease.

The Various Clinical Manifestations of Tularemia

The bacterium’s remarkable adaptability allows it to infect humans through various portals of entry, leading to distinct clinical manifestations. I consider it one of the “great imitators” due to its 6 primary forms--glandular, oculo-glandular, ulcero-glandular, oropharyngeal, pulmonic, and typhoidal. These forms present in completely different ways and can fool the clinician if there is not a high index of suspicion. Despite my regularly teaching healthcare practitioners about tularemia, it took me 4 hours during an initial history and physical of the patient described below to come up with the diagnosis because the presentation and history was so complex.

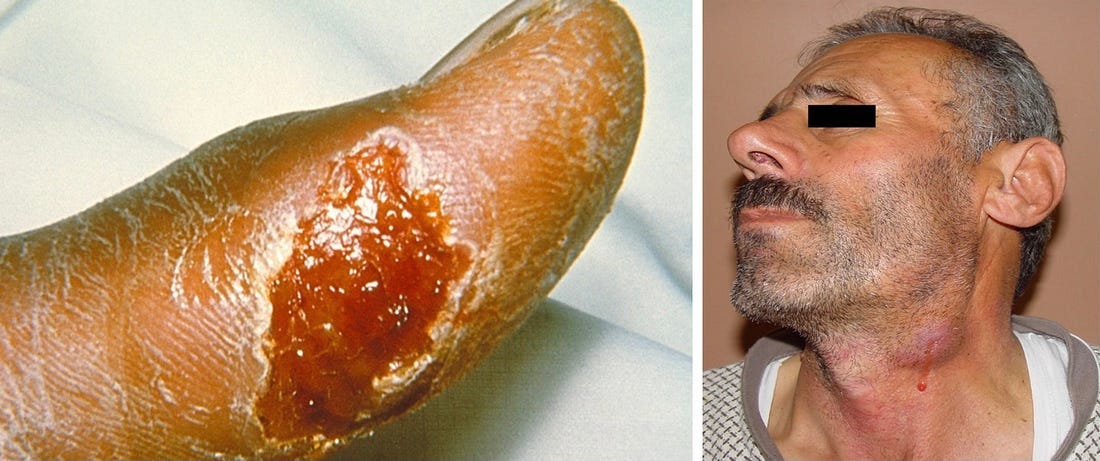

Form #1: Ulceroglandular Tularemia

This is the most common form, accounting for 75-85% of reported cases. It’s typically caused by a bite from an infected arthropod (ticks, deerflies) or direct contact with infected animal tissues (e.g. during hunting or skinning). The incubation period is 3-5 days but can be 1-14 days, with an acute symptom onset. The hallmark of this form is the development of a painful, often punched-out ulcer at the site of the bite, accompanied by swollen lymph nodes nearby, as you can see here:

The ulcer usually appears 2-5 days after exposure, starting as a raised, red papule that progresses to a pustule and then ulcerates. The regional lymph nodes, most commonly in the armpit or groin, become swollen, tender, and may suppurate (fill with pus), forming abscesses. Systemic symptoms of fever, chills, headaches, malaise, and fatigue are common. The diagnosis is suspected based on the characteristic ulcer and regional lymph node involvement for those with a relevant exposure history.

Form #2: Glandular Tularemia

The glandular form is essentially ulceroglandular tularemia without the ulcer. The bacterium usually gains entry through a microscopic lesion on the skin, or sometimes by inhalation. The primary manifestation is when large regional lymph nodes become swollen, tender, and potentially purulent. Systemic symptoms including fever, chills, and malaise are also present. Diagnosis can be challenging without a high index of suspicion, because many different diseases (like EBV, lymphoma, etc.) cause enlarged lymph nodes with fever, chills, and fatigue.

Form #3: Oculoglandular Tularemia.

This is caused F. tularensis getting into the conjunctiva of the eye via contaminated fingers, splashes of contaminated fluids, or by rubbing the eyes after handling infected animals. Symptoms typically include acute unilateral conjunctivitis, characterized by redness, pain, tearing, and sensitivity to light. Small, yellowish nodules or ulcers may develop on the conjunctiva. Like other forms, there are often concurrent swollen lymph nodes in front of the ears, below the chin, or in the neck, as you can see:

If left untreated, the conjunctivitis can become chronic and cause corneal ulceration or perforate the eye. Confirmatory testing is crucial due to different causes of conjunctivitis.

Form #4: Oropharyngeal Tularemia

Ingesting contaminated food or water can lead to pharyngitis, tonsillitis, and swollen lymph nodes in the neck. Patients can also develop mouth ulcers with a sore throat, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The symptoms mimic strep pharyngitis or infectious mononucleosis.

Low tularemia titers can turn positive when treatment with multiple antibiotics (like dapsone combination therapy, using doxycycline, rifampin, dapsone and especially pyrazinamide) flushes the bacteria out of hiding. In one of my most severe autoimmune cases—a patient with Lyme, Babesia, Bartonella, tularemia, andBehçet'sdisease--the ulcers from Behçet's improved after this treatment, but also caused a reactivation of tularemia, with titers rising 4-fold. The tongue ulcers resolved after this protocol was finished, as you can see here:

Form #5: Pneumonic Tularemia

This is the most severe, life-threatening form, primarily following inhalation of aerosolized F. tularensis or secondarily through human touch from another site of infection. Inhalation can occur during agricultural activities, landscaping (mowing over a dead rabbit), or laboratory accidents. It is most often seen in the Martha’s Vineyard area where tularemia is also aerosolized by the seawater. The New England Journal of Medicine published a case series years ago where they identified 15 patients with tularemia; 11 of these cases were primary pneumonic tularemia. Francisella tularensis type A was isolated from blood and lung tissue of one man who died, and patients often used a lawnmower or brush cutter 2 weeks before the illness.

Symptoms are nonspecific and can include fever, chills, headache, malaise, a dry cough, and pleuritic chest pain (chest pain upon taking a deep breath). Chest x-rays often reveal pneumonia-type changes with fluid (pleural effusions), which are common. Without prompt and appropriate treatment, pneumonic tularemia can rapidly progress to respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome, with a high mortality rate. Due to severe outcomes with a nonspecific presentation, and ability of the organism to be aerosolized, pneumonic tularemia is a significant concern in bio-defense scenarios.

Form #6: Typhoidal Tularemia

This form is often characterized by high fever, chills, profound malaise, headache, myalgias, and weight loss with gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. An enlarged liver and spleen may also be present. The lack of a localized lesion makes diagnosis challenging, as the symptoms are nonspecific, mimicking many other febrile illnesses, including typhoid fever, malaria, and sepsis. This form carries a significant risk of complications, including multiorgan failure if not properly diagnosed and treated.

Diagnosing Tularemia

Diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion, epidemiological history, and laboratory confirmation. Culture of F. Tularensis is the gold standard for diagnosis, but it can be difficult and dangerous due to slow growth of the bacterium and risk to laboratory workers. Specimens can be obtained from ulcers, lymph node aspirates, sputum, or blood depending on the clinical form. Most laboratories, because of biosafety concerns, do not routinely culture F. tularensis.

Blood tests are most commonly used. A microagglutination test (MAT) and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detect F. tularensis antibodies. A 4-fold rise in antibody titers between acute and convalescent specimens, or single high titer is indicative of infection. However, antibodies may not be detectable in early stages of the disease, leading to false negatives. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test offers a rapid and sensitive means of detection in early stages. Immunofluorescent assays can also be used to detect bacterial antigens in tissue samples. False positive reactions and cross-reactive serological titers can occur with Bartonella spp., as well as Brucella spp. (I see this frequently). Doing a Bartonella Immunoblot, FISH, PCRs, and Brucella agglutination test can help confirm the source.

Treating Tularemia

Streptomycin (15 mg/kg intramuscular every 12 hours) or Gentamycin (1.5 mg IV every 8 hours) for 10 days with dose adjustment for renal function is the standard of care for severe tularemia, including pneumonic, typhoidal, or severe ulceroglandular forms. For mild to moderate tularemia, such as uncomplicated ulceroglandular, glandular, oculoglandular or oropharyngeal forms, doxycycline 100 milligrams 2x/day with or without a fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin 500 mg-750 mg 2x/day or levofloxacin 500 mg 2x/day are also effective alternatives. Fluoroquinolones may be considered if aminoglycosides are contraindicated or unavailable. Surgical drainage may be necessary if lymph nodes are filled with pus or abscesses are present. Prompt initiation of antibiotics is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality, and relapse rates are higher among tetracyclines compared to aminoglycosides or fluroquinolones, if treatment is delayed or not long enough.

[Natural Remedies may include:

If pharmaceutical antibiotics like streptomycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, or ciprofloxacin are not for you, consider:

⚠️ Always discuss these with a healthcare provider first. Never DIY with this disease.

🌿 Herbal Supportive Options:

Herb Echinacea May stimulate the immune system

Astragalus Immune tonic; may support recovery

Andrographis Antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects

Garlic (Allicin) Antibacterial properties; immune support

Turmeric (Curcumin) Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant

Olive Leaf Extract Antimicrobial and immune supportive

Use of Healing Peptides for skin healing and antimicrobial (BPC157, KPV, LL-37)

Immune enhancers: LDN, Med.Mushrooms, BioCidin and others.

✅ Supportive Nutrition Tips

Hydration: Crucial during fever or infection.

Vitamin C and Zinc: Support immune response. Helps with skin and soft tissue healing and enhances the immune system.

Probiotics: To replenish gut flora, especially if you're on antibiotics.]

What Can Happen When You’re Misdiagnosed

Steven was a 40-year-old chef who came to me after being sick for 4 years. Multiple evaluations at major medical centers failed to find the root cause of his symptoms, even after biopsy and culture of his lymph nodes and ulcers with a thorough GI evaluation. In the past, he’d suffered from retroperitoneal fibrosis with renal failure, requiring stents in his kidneys. His chief complaints included severe fatigue, headaches, night sweats, loss of libido, joint and muscle pains, and memory and concentration problems, and he developed painful ulcers on his lower extremities which would come and go. His other doctors thought he had an atypical form of inflammatory bowel disease, yet his colonoscopy was negative. You can see the healed ulcer above the open one:

Stephen had gotten tularemia from a tick bite as well as from skinning rabbits while working as a chef. His Lyme, Babesia, Bartonella, and tularemia responded well to doxycycline, rifampin, and dapsone. All his ulcers cleared, and his kidney function returned to normal, so his stents could be removed. He is now much better post-treatment.

Tularemia is definitely a great imitator! If you’re being tested for any TBD, don’t be surprised at how often titers are positive. Be vigilant!

Other great posts by Dr. Horowitz on Substacks on Lyme & TBDz:

Babesia:

Bartonella:

Ehrlichia/Anaplasma:

Medical Detective is a reader-supported publication. This Substack is Follow-Worthy!